| |

For those who might question the seriousness of the issue of propaganda in movies, there is the case of Ayn Rand's testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Rand was famously ambiguous about the propriety of such a committee. (She need not have been, there is no such thing as the freedom to initiate political violence, something which the supporters of communism and sharia have in common.) So what topic was so important to her that she felt it necessary to speak to Congress?

The topic was communist propaganda in films. The specific film which she criticized was Song of Russia, which dealt with an American symphony touring Russia. Surely an innocent topic which one could simply relax and enjoy?

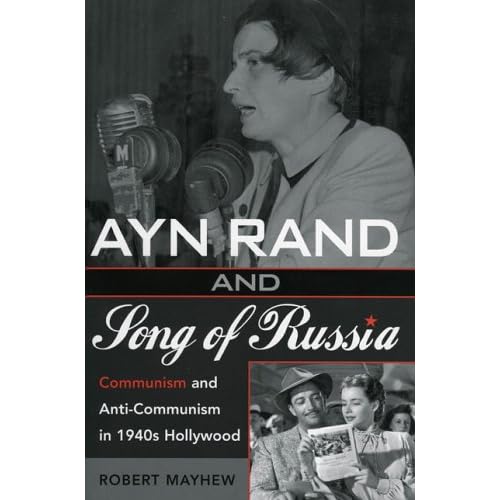

A book has been written on the matter by Robert Mayhew. Ayn Rand and Song of Russia: Communism and Anti-Communism in 1940s Hollywood By Robert Mayhew. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2005.

Here is an article providing a comprehensive review of Mayhew's book addressing the historical context from Mises.org.

Rand's testimony and a description of its context is available at NobleSoul.com. An excerpt:

At the time she was called to testify, Rand was already well-known in Hollywood for her opposition to Communism. She originally planned to testify about two movies -- Song of Russia and The Best Years of Our Lives. The former was made during World War II, with the fairly obvious purpose of making Americans feel more comfortable about being allies with the Soviets during the war. The latter was a popular post-war film that had won several Academy Awards, including the Oscar for best picture. Rand was later asked to testify only about Song of Russia. Some members of the committee thought it was too risky to criticize a popular film like The Best Years of Our Lives. Upset by that she was only allowed to discuss one older movie that was obvious propaganda, Rand demanded a chance to give additional testimony. After some argument, Chairman Thomas eventually offered to recall her later in the hearings. He never did recall her. Her testimony as it stands concerns only Song of Russia.

And here is a partial excerpt of Rand's testimony copied from the full annotated transcript at Noble Soul:

Stripling: Could you talk into the microphone?

Rand: Can you hear me now? Nobody has stated just what they mean by propaganda. Now, I use the term to mean that Communist propaganda is anything which gives a good impression of communism as a way of life. Anything that sells people the idea that life in Russia is good and that people are free and happy would be Communist propaganda. Am I not correct? I mean, would that be a fair statement to make -- that that would be Communist propaganda?

Now, here is what the picture Song of Russia contains. It starts with an American conductor, played by Robert Taylor,14 giving a concert in America for Russian war relief. He starts playing the American national anthem and the national anthem dissolves into a Russian mob, with the sickle and hammer on a red flag very prominent above their heads. I am sorry, but that made me sick. That is something which I do not see how native Americans permit, and I am only a naturalized American. That was a terrible touch of propaganda. As a writer, I can tell you just exactly what it suggests to the people. It suggests literally and technically that it is quite all right for the American national anthem to dissolve into the Soviet. The term here is more than just technical. It really was symbolically intended, and it worked out that way. The anthem continues, played by a Soviet band. That is the beginning of the picture.

Now we go to the pleasant love story. Mr. Taylor is an American who came there apparently voluntarily to conduct concerts for the Soviets. He meets a little Russian girl15 from a village who comes to him and begs him to go to her village to direct concerts there. There are no GPU16 agents and nobody stops her. She just comes to Moscow and meets him. He falls for her and decides he will go, because he is falling in love. He asks her to show him Moscow. She says she has never seen it. He says, "I will show it to YOU." They see it together. The picture then goes into a scene of Moscow, supposedly. I don't know where the studio got its shots, but I have never seen anything like it in Russia. First you see Moscow buildings -- big, prosperous-looking, clean buildings, with something like swans or sailboats in the foreground. Then you see a Moscow restaurant that just never existed there. In my time, when I was in Russia, there was only one such restaurant, which was nowhere as luxurious as that and no one could enter it except commissars and profiteers. Certainly a girl from a village, who in the first place would never have been allowed to come voluntarily, without permission, to Moscow, could not afford to enter it, even if she worked ten years. However, there is a Russian restaurant with a menu such as never existed in Russia at all and which I doubt even existed before the revolution. From this restaurant they go on to this tour of Moscow. The streets are clean and prosperous-looking. There are no food lines anywhere. You see shots of the marble subway -- the famous Russian subway out of which they make such propaganda capital. There is a marble statue of Stalin thrown in. There is a park where you see happy little children in white blouses running around. I don't know whose children they are, but they are really happy kiddies. They are not homeless children in rags, such as I have seen in Russia. Then you see an excursion boat, on which the Russian people are smiling, sitting around very cheerfully, dressed in some sort of satin blouses such as they only wear in Russian restaurants here. Then they attend a luxurious dance. I don't know where they got the idea of the clothes and the settings that they used at the ball and --

Stripling: Is that a ballroom scene?

Rand: Yes; the ballroom -- where they dance. It was an exaggeration even for this country. I have never seen anybody wearing such clothes and dancing to such exotic music when I was there. Of course, it didn't say whose ballroom it is or how they get there. But there they are -- free and dancing very happily.

Incidentally, I must say at this point that I understand from correspondents who have left Russia and been there later than I was and from people who escaped from there later than I did that the time I saw it, which was in 1926, was the best time since the Russian revolution. At that time conditions were a little better than they have become since. In my time we were a bunch of ragged, starved, dirty, miserable people who had only two thoughts in our mind. That was our complete terror -- afraid to look at one another, afraid to say anything for fear of who is listening and would report us -- and where to get the next meal. You have no idea what it means to live in a country where nobody has any concern except food, where all the conversation is about food because everybody is so hungry that that is all they can think about and that is all they can afford to do. They have no idea of politics. They have no idea of any pleasant romances or love-nothing but food and fear. That is what I saw up to 1926. That is not what the picture shows.

Now, after this tour of Moscow, the hero -- the American conductor -- goes to the Soviet village. The Russian villages are something -- so miserable and so filthy. They were even before the revolution. They weren't much even then. What they have become now I am afraid to think. You have all read about the program for the collectivization of the farms in 1933, at which time the Soviet Government admits that three million peasants died of starvation. Other people claim there were seven and a half million, but three million is the figure admitted by the Soviet Government as the figure of people who died of starvation, planned by the government in order to drive people into collective farms. That is a recorded historical fact.17

Now, here is the life in the Soviet village as presented in Song of Russia. You see the happy peasants. You see they are meeting the hero at the station with bands, with beautiful blouses and shoes, such as they never wore anywhere. You see children with operetta costumes on them and with a brass band which they could never afford. You see the manicured starlets driving tractors and the happy women who come from work singing. You see a peasant at home with a close-up of food for which anyone there would have been murdered. If anybody had such food in Russia in that time he couldn't remain alive, because he would have been torn apart by neighbors trying to get food. But here is a close-up of it and a line where Robert Taylor comments on the food and the peasant answers, "This is just a simple country table and the food we eat ourselves."

Then the peasant proceeds to show Taylor how they live. He shows him his wonderful tractor. It is parked somewhere in his private garage. He shows him the grain in his bin, and Taylor says, "That is wonderful grain." Now, it is never said that the peasant does not own this tractor or this grain because it is a collective farm. He couldn't have it. It is not his. But the impression he gives to Americans, who wouldn't know any differently, is that certainly it is this peasant's private property, and that is how he lives, he has his own tractor and his own grain. Then it shows miles and miles of plowed fields.

Chairman Thomas: We will have more order, please.

Rand: Am I speaking too fast?

Chairman Thomas: Go ahead.

Rand: Then --

Stripling: Miss Rand, may I bring up one point there?

Rand: Surely.

Stripling: I saw the picture. At this peasant's village or home, was there a priest or several priests in evidence?

Rand: Oh, yes; I am coming to that, too. The priest was from the beginning in the village scenes, having a position as sort of a constant companion and friend of the peasants, as if religion was a natural accepted part of that life. Well, now, as a matter of fact, the situation about religion in Russia in my time was, and I understand it still is, that for a Communist Party member to have anything to do with religion means expulsion from the party. He is not allowed to enter a church or take part in any religious ceremony. For a private citizen, that is a nonparty member, it was permitted, but it was so frowned upon that people had to keep it secret, if they went to church. If they wanted a church wedding they usually had it privately in their homes, with only a few friends present, in order not to let it be known at their place of employment because, even though it was not forbidden, the chances were that they would be thrown out of a job for being known as practicing any kind of religion.18

Now, then, to continue with the story, Robert Taylor proposes to the heroine. She accepts him. They have a wedding, which, of course, is a church wedding. It takes place with all the religious pomp which they show. They have a banquet. They have dancers, in something like satin skirts and performing ballets such as you never could possibly see in any village and certainly not in Russia. Later they show a peasants' meeting place, which is a kind of a marble palace with crystal chandeliers. Where they got it or who built it for them I would like to be told. Then later you see that the peasants all have radios. When the heroine plays as a soloist with Robert Taylor's orchestra, after she marries him, you see a scene where all the peasants are listening on radios, and one of them says, "There are more than millions listening to the concert."

I don't know whether there are a hundred people in Russia, private individuals, who own radios. And I remember reading in the newspaper at the beginning of the war that every radio was seized by the government and people were not allowed to own them. Such an idea that every farmer, a poor peasant, has a radio, is certainly preposterous. You also see that they have long-distance telephones. Later in the picture Taylor has to call his wife in the village by long-distance telephone. Where they got this long-distance phone, I don't know.

Now, here comes the crucial point of the picture. In the midst of this concert, when the heroine is playing, you see a scene on the border of the U.S.S.R. You have a very lovely modernistic sign saying "U.S.S.R." I would just like to remind you that that is the border where probably thousands of people have died trying to escape out of this lovely paradise. It shows the U.S.S.R. sign, and there is a border guard standing. He is listening to the concert. Then there is a scene inside kind of a guardhouse where the guards are listening to the same concert, the beautiful Tschaikowsky music, and they are playing chess.

Suddenly there is a Nazi attack on them. The poor, sweet Russians were unprepared. Now, realize -- and that was a great shock to me -- that the border that was being shown was the border of Poland. That was the border of an occupied, destroyed, enslaved country which Hitler and Stalin destroyed together.19 That was the border that was being shown to us -- just a happy place with people listening to music.

Also realize that when all this sweetness and light was going on in the first part of the picture, with all these happy, free people, there was not a GPU agent among them, with no food lines, no persecution -- complete freedom and happiness, with everybody smiling. Incidentally, I have never seen so much smiling in my life, except on the murals of the world's fair pavilion of the Soviets. If any one of you have seen it, you can appreciate it. It is one of the stock propaganda tricks of the Communists, to show these people smiling. That is all they can show. You have all this, plus the fact that an American conductor had accepted an invitation to come there and conduct a concert, and this took place in 1941 when Stalin was the ally of Hitler. That an American would accept an invitation to that country was shocking to me, with everything that was shown being proper and good and all those happy people going around dancing, when Stalin was an ally of Hitler.

Now, then, the heroine decides that she wants to stay in Russia. Taylor would like to take her out of the country, but she says no, her place is here, she has to fight the war. Here is the line, as nearly exact as I could mark it while watching the picture:

"I have a great responsibility to my family, to my village, and to the way I have lived."

What way had she lived? This is just a polite way of saying the of life. She goes on to say that she wants to stay in the country because otherwise, "How can I help to build a better and better life for my country." What do you mean when you say better and better? That means she has already helped to build a good way. That is the Soviet Communist way. But now she wants to make it even better. All right.

Now, then, Taylor's manager, who is played, I believe, by Benchley20, an American, tells her that she should leave the country, but when she refuses and wants to stay, here is the line he uses: he tells her in an admiring friendly way that "You are a fool, but a lot of fools like you died on the village green at Lexington."21

Now, I submit that that is blasphemy, because the men at Lexington were not fighting just a foreign invader. They were fighting for freedom and what I mean -- and I intend to be exact -- is they were fighting for political freedom and individual freedom. They were fighting for the rights of man. To compare them to somebody, anybody fighting for a slave state, I think is dreadful. Then, later the girl also says -- I believe this was she or one of the other characters -- that "the culture we have been building here will never die." What culture? The culture of concentration camps.22

At the end of the picture one of the Russians asks Taylor and the girl to go back to America, because they can help them there. How? Here is what he says, "You can go back to your country and tell them what you have seen and you will see the truth both in speech and in music." Now, that is plainly saying that what you have seen is the truth about Russia. That is what is in the picture.

Now, here is what I cannot understand at all: if the excuse that has been given here is that we had to produce the picture in wartime, just how can it help the war effort? If it is to deceive the American people, if it were to present to the American people a better picture of Russia than it really is, then that sort of an attitude is nothing but the theory of the Nazi elite -- that a choice group of intellectual or other leaders will tell the people lies for their own good. That I don't think is the American way of giving people information. We do not have to deceive the people at any time, in war or peace. If it was to please the Russians, I don't see how you can please the Russians by telling them that we are fools. To what extent we have done it, you can see right now. You can see the results right now. If we present a picture like that as our version of what goes on in Russia, what will they think of it? We don't win anybody's friendship. We will only win their contempt, and as you know the Russians have been behaving like this.

My whole point about the picture is this: I fully believe Mr. Mayer when he says that he did not make a Communist picture. To do him justice, I can tell you I noticed, by watching the picture, where there was an effort to cut propaganda out. I believe he tried to cut propaganda out of the picture, but the terrible thing is the carelessness with ideas, not realizing that the mere presentation of that kind of happy existence in a country of slavery and horror is terrible because it is propaganda. You are telling people that it is all right to live in a totalitarian state.

Now, I would like to say that nothing on earth will justify slavery. In war or peace or at any time you cannot justify slavery. You cannot tell people that it is all right to live under it and that everybody there is happy. If you doubt this, I will just ask you one question. Visualize a picture in your own mind as laid in Nazi Germany. If anybody laid a plot just based on a pleasant little romance in Germany and played Wagner music and said that people are just happy there, would you say that that was propaganda or not, when you know what life in Germany was and what kind of concentration camps they had there. You would not dare to put just a happy love story into Germany, and for every one of the same reasons you should not do it about Russia.

(Edited by Ted Keer on 12/30, 5:26pm)

|

|